By: Jay A. Carizo

The Mandanas-Garcia Ruling mandates the expansion of the income base for the computation of the national tax allocation (NTA) for local government units (LGUs) to include not only internal revenue collections but also customs collections. This assures LGUs with an additional 24% revenue share aside from the 13.9% increase due to the increase in internal revenue collections. The figures look appealing especially for NTA-dependent LGUs like the barangays. But how does this really look like in its first year’s implementation? Will the amount be enough to cover the devolved functions and services that the barangays need to deliver by virtue of the Executive Order No. 138?

To answer these questions, I looked into Northern Samar as a focus province. Northern Samar is one of the provinces in the Philippines known for cutting poverty incidence by more than half from 51.8% in 2015 to 25.1% in the first semester of 2021. As a result, the province was stricken out of the list of the top 20 poorest provinces in the country.[1]

Northern Samar has a readily available barangay-level national tax allocations data for fiscal years 2021 and 2022 making it possible for a pre- and during- the Mandanas-Garcia Ruling comparison. Hence, the focus province for this discussion note.

The Gainers and Not-so Gainers

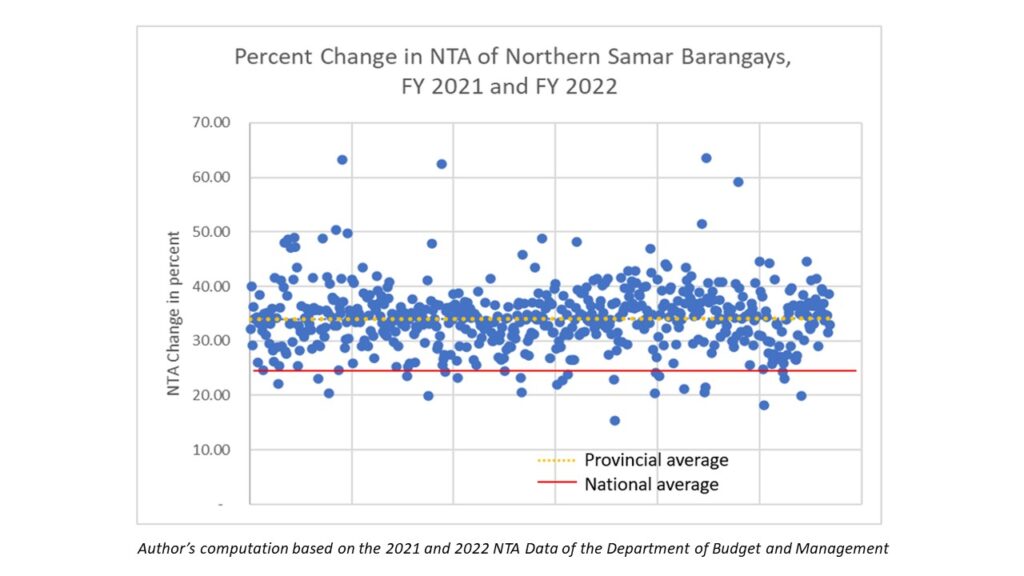

Northern Samar has 24 municipalities and 569 barangays. On the average, the barangay LGUs enjoy a 34.11% NTA increase as against the 24% increase at the national level.

Six of the barangays in the province enjoys more than 50% increase in NTA from 2021 to 2022. Two of these are in the Pambujan municipality (Poblacion 8 and Poblacion 4 with 63.48% and 50.54% increases, respectively), two are in Catarman (Macagtas and Kasoy with 63.28% and 50.38%, respectively), one in Laoang (Bgy. Aguadahan with 62.42%) and one in San Isidro (Happy Valley with 59.23%).

Not all, however, enjoy high NTA increases. Twenty-one of the barangays received NTA increases that are below the national average of 24%. Four of these are in Las Navas; three in Palapag; two each in Catarman, Lope de Vega and Pambujan; while the rest are from Catubig, Laoang, San Vicente, Biri, Gamay, Silvino Lobos and San Roque.

A total of 191 barangays were able to receive more than PhP 773,609.08 – the computed average NTA increase. Four were able to receive more than PhP 2 million and these are Poblacion District 8 in Pambujan, and Barangays Baybay, Macagtas and Dalakit all in Catarman.

Twenty-three received less than half a million-peso additional NTA. The bottom five are Upper Caynaga in Lope de Vega with only PhP 286,135.00 additional funds; Gamay Occidental 1 in Gamay with PhP 376,809.00; Somoroy in Lope de Vega with PhP 381,254.00; Chansvilla in Lavezares with PhP 388,240.00; and Bangon in Palapag with PhP 427,592.00.

Clearly, the increase in NTA is not across the board. It still follows the formula laid down in Section 285 of the Local Government Code of 1991 which considers the population and equal sharing arrangements.

Perspectives of Barangay Officials

Given the increases, are the additional NTAs of the barangays enough?

Unfortunately, the answer is No. For the local officials in island barangays, the question is even more of: Where is the NTA? Officials interviewed from these barangays say they are expecting an annual NTA increase, so what they received in 2022 is simply part of what they ought to have received.

For those living in the mainland, especially those classified as urban barangays, the NTAs are not enough, and the increase is not commensurate with the functions that they must perform and services they need to deliver. During the COVID-19 pandemic, for example, the barangay officials had to face not only a health issue but a complex event that highlighted the problems in education, economy and livelihood, and peace and order, among others. This was compounded by the lockdowns and community quarantines that limited mobility and compelled their constituents working outside the province to return home. Hence, the population that they needed to serve increased, most of whom were rendered jobless.

The sudden increase of the population without the corresponding hike in income figures became the biggest challenge among barangay officials. This resulted not only to a loss of the already paltry revenues the barangay LGUs have been collecting but also created acrimonious situations. As more and more found themselves unemployed, many became irritable and would sometimes pick quarrels with local officials who became easy targets to vent their anger and frustration especially since the barangay LGUs were at the frontlines in distributing food packs and other COVID-19-related assistance.

Next to this is the issue surrounding the education sector. While barangay LGUs are not directly involved in the provision of education-related services, they are still expected to contribute to the supply side so that the schools and child development centers will be able to effectively function. A number of barangay officials claim that their LGUs were tapped by schools so that the latter will be able to satisfy the requirements in the Safe Schools Assessment Tool (SSAT). The SSAT is a list of 172 indicators that needs to be satisfied for schools to physically reopen.

“The schools have limited funds so we have to pitch in with whatever we can provide”, claims Nolito Odtujap, the Punong Barangay of Aguin, Capul. “Otherwise, our schools will not reopen,” he continued.

In addition, the barangay LGUs are responsible for the safety of the students when they leave their homes for school and when they leave school to go back to their homes. The safety and security of children inside their homes are the purview of the parents; while in school, the responsibility is passed on to schoolteachers and officials. The period in between the home and the school is the concern of the barangay LGU.

“We have to ensure that the children are safe on their way to and from the school. Thus, we have to deploy more barangay tanods and officials, and provide for the necessary health and hygiene kits,” adds Lerma Cula of Barangay Sagaosawan, also in Capul. But while some of those helping to ensure the safety of the children only receive honorarium, health and hygiene-related kits and facilities need to be procured, which became an additional burden for Sagaosawan since it only has around PhP 1.6 million NTA as of 2021. This is also the case in Barangay Chansvilla in Lavesares that has an NTA of PhP 1.46 million, the barangay that has the smallest NTA in the province.

Barangay officials, however, are worried especially in the coming fiscal years from 2023 to 2025 when the NTA is expected to decrease due to COVID-19. Initial computation released by the Department of Budget and Management shows that LGU NTAs would be reduced by around 14% and for in Northern Samar, this means an average reduction of around PhP 427,000 per barangay LGU.

What needs to be done

All of the barangays in Northern Samar are NTA-dependent albeit on varying degrees. In the short term, these LGUs need technical and financial assistance from the municipal and provincial governments as well as national government agencies. For the technical assistance, barangay officials request policy guidance and capacity development on how to effectively manage the meager resources of their LGUs.

Reviving the economy to generate more income both for the population and the LGU while exercising the minimum health protocols should also be considered a priority. Easing the health restrictions especially in municipalities that are not affected by COVID-19 should be implemented since this will allow people to work and generate income.

For the long term, barangay LGUs also need assistance on how to veer away from NTA-dependency. National government agencies could provide technical support on how this can be done that can be reinforced by examples from LGUs that are no longer NTA-dependent.

Revisit the NTA allocation, a clamor from several barangay officials. The current NTA is population-dependent, but the population statistics is only updated every five years and does not consider shocks similar to the COVID-19 pandemic. When the economy ground to a halt, people returned to their barangays but the allocation that the barangay LGUs received was based on pre-pandemic situations. Hence, they could not cope up with the demands of their current constituents.

Another is the need to look beyond the number of population but also on the quality of life of the constituents and other data sets to make the tax allocation equitable and effective. This will also ensure that that the increases will go to the barangay LGUs that need them most. After all, these are resources that each Filipino gives to the government–taxes and customs collection–that should be used to improve every Filipino’s life.

Lastly, ensure that the NTA data are released publicly and on time. Judicious use of limited resources is possible through use of data in planning and prioritization and an early information on the budget available could lessen the pressure on the LGUs. Public release of the data can also encourage stakeholders to help LGUs in project planning and prioritization similar to the bottom-up budgeting program in 2021-2016. Knowledge on how much resources are available encouraged the community members to participate in the planning and budgeting process.

[1] Marticio, Marie Tonette. (2022). “N. Samar no longer part of country’s poorest provinces” in https://mb.com.ph/2022/01/17/n-samar-no-longer-part-of-countrys-20-poorest-provinces/. Accessed on June 29, 2022.